Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

They’re quiet, sneaky, and often backed by powerful countries, making them a serious and lasting threat to important targets.

APT groups use special malware and can hide inside systems for months without being noticed. They’re not after quick cash, they want secrets and important info.

Unlike regular hackers, APTs go after big things like governments, power systems, and large companies. And they’re patient, they’ll wait and watch for years to get what they’re after.

There is something almost methodical about the way an APT group moves through a network. Not rushed, not sloppy. In fact, APT dwell times, how long they remain undetected, often span months (1).

Industry reports place the average global dwell time around 95 days, with many campaigns stretching well beyond that. In one infamous case, attackers from the SolarWinds breach remained active for over a year before being discovered.

If you’ve ever seen a security team deal with a live break-in, you might notice how quiet the room gets. It feels like someone out there, calm, careful, and well-prepared, is checking off each step of a plan.

APT groups aren’t like regular hackers. They’re patient, have lots of support, and know exactly what they’re doing.. Their operations are closer to intelligence work than smash-and-grab thefts.

Source: Huntress

At the heart of advanced persistent threat groups are three big traits: they’re smart, they don’t give up, and they go after specific targets.

They use tricky tools, like hidden bugs and special malware, to quietly sneak into systems without being seen. Nearly half, 48%, of them leverage legitimate admin tools to ‘live off the land’, blending malicious activity with normal operations (2).

What makes them really dangerous is how long they stay. Their persistence, called dwell time, means they can hang around for weeks, months, or even years, keeping a secret way back in.

The targets are never random. Every campaign is aimed at extracting specific intelligence or causing disruption.

Most regular hackers just throw out attacks and hope someone falls for them. It’s like casting a big net and seeing what they catch.

APT groups don’t work that way. They take their time. They spy first, then go after big important places like government offices, military, or the systems that keep our lights on and water running.

They don’t send out random emails either. They use something called spear phishing, emails that feel real, with details only someone on the inside would know. The big difference? APTs are patient, careful, and very focused.

Most people, even those working in IT, underestimate the range of targets APTs select. It is not just military secrets or nuclear codes.

Sometimes it is the formula for a new drug, the blueprints for an energy grid, or the emails of political operatives.

The bulk of APT activity centers on high-value targets:

I once sat with an incident response team at a major energy company. Their logs showed the hackers had spent months quietly stealing usernames and passwords.

Then, all of a sudden, they started trying to gain more access and take control of bigger parts of the system. The adversary was not interested in quick payouts, they wanted control.

Stealing secrets from governments is still a big goal, but money matters too. These days, hackers working for governments don’t just try to steal secret plans.

They also try to take business ideas, new inventions, and research to help their own country’s companies do better.

Sometimes, spying on companies is the main goal. The pattern is easy to see: if information is valuable for the future, APT groups will try to get it.

Credit: pexels.com (Photo by Pixabay)

It is rare for a single tactic to bring down a major target. Instead, APT operations unfold in a sequence, each stage building on the last.

Most APT attacks start with spear phishing. That means the hackers send a fake email that looks real, with a bad link or file that can break into the system.

Sometimes, they get in through a secret bug, called a zero-day, in websites or tools people use. Other times, they sneak in through a trusted supplier, like part of a supply chain.

These initial breaches are silent. The attacker’s goal is to get one foot in the door without triggering alarms.

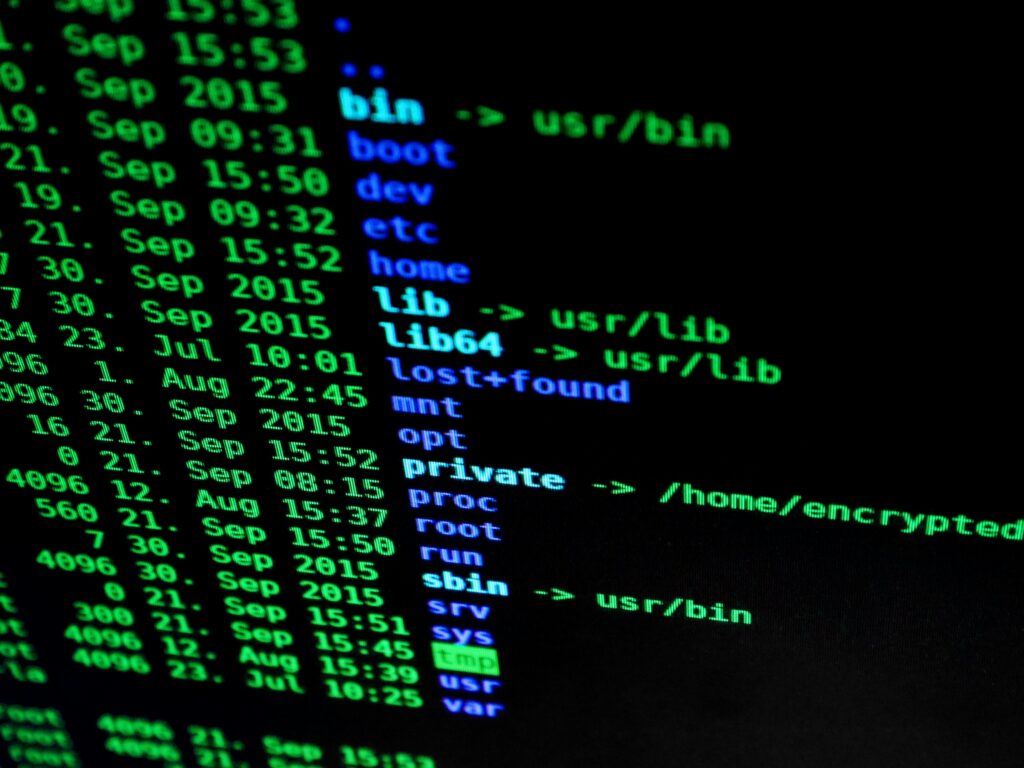

Once inside, the hackers build a secret way to talk to the infected system. This is called command and control, or C2. They often use special malware or a remote access trojan (RAT) to do it.

Next comes lateral movement. That means they explore the network, try to get more power, and move from one computer to another. They also create backup ways to get in later.

Sometimes they use normal system tools to hide what they’re doing, this trick is called living off the land. It helps them blend in and stay hidden.

After the hackers find important stuff, like emails, files, or databases, they start to steal it. This is called data exfiltration. They do it slowly, sending out little bits at a time so no one notices.

In one case I looked at, the attackers spent weeks gathering and packing the files. Then, while everyone was distracted by a loud attack that shut things down, they quietly sent the stolen data out overnight.

Persistence is a hallmark of APTs. Hackers set up more than one secret way back into the system, just in case one gets found.

They also steal passwords and try to get more control by raising their access levels.

This way, they make sure they can stay in and keep coming back, even if someone tries to block them. Even if one route is closed, another remains open, sometimes for years.

APT groups rarely operate in the open, but their handiwork is sometimes unmistakable. The names, Fancy Bear, Cozy Bear, OceanLotus, sound almost whimsical, but their operations are anything but.

APT28 and APT29, both linked to Russian intelligence, have targeted NATO governments, political campaigns, and energy infrastructure.

APT29, or Cozy Bear, was behind the SolarWinds supply chain attack, a breach that compromised thousands of organizations.

APT1 specialized in industrial espionage, targeting U.S. manufacturers for years. APT41 (Wicked Panda) is notable for combining espionage with financially motivated attacks, hitting video game companies, healthcare, and telecoms.

Lazarus Group, attributed to North Korea, mixes cyber espionage with ransomware and banking theft. APT32 (OceanLotus) focuses on Southeast Asian governments and dissidents, while APT34 (Helix Kitten) is active in the Middle East, mainly targeting energy and telecom sectors.

The SolarWinds hack is a textbook example. Attackers compromised Orion software updates, gaining entry to U.S. government agencies and Fortune 500 companies. They used advanced evasion techniques, zero-day exploits, and stealthy lateral movement to remain undetected for months.

APT41’s campaigns show how the line between espionage and cybercrime blurs. The group used spear phishing and custom malware loaders to steal R&D data from pharma companies, then pivoted to ransomware attacks for profit.

If you look at enough incident reports, certain tactics repeat.

Targeted emails remain the most reliable entry point. Attackers research their victims, crafting messages that look authentic. Social engineering extends to phone calls and even in-person visits in rare cases.

APTs rarely use off-the-shelf malware. Instead, they build custom payloads, malware campaigns tailored to bypass defenses. Living off the land means they use tools already present in the environment, like PowerShell or WMI, making detection difficult.

Redundancy is everything. Attackers maintain several access vectors, set up C2 servers in cloud environments, and use encryption to hide traffic.

Operational security is tight. Communications are time-delayed, and malware is self-deleting or re-encrypting on command.

No single solution works. Defense is layered and constant.

Organizations rely on MSSP-driven security fundamentals like endpoint detection and response (EDR) tools, network monitoring, and threat intelligence feeds.

Behavioral analytics flag unusual activity, like a legitimate admin account logging in at 3 a.m. from an overseas IP.

Continuous monitoring is the only way to catch dwell time. Machine learning models learn what normal traffic looks like, so anomalies stand out.

Many firms now have dedicated threat hunting teams. They search for indicators of compromise (IoCs), reviewing logs for subtle signs: a registry change here, a suspicious process there.

Network segmentation limits lateral movement. Least privilege access policies mean one compromised credential cannot open every door. Regular vulnerability management patches weak points before they are exploited.

Most breaches begin with a person. Accessing outside security expertise through training programs, simulated phishing campaigns, and clear incident reporting processes makes a difference.

Even the best defenses fail. What you do next matters.

When an APT is detected, teams move quickly to isolate affected systems and cut off C2 traffic. Containment is measured in minutes, not hours.

Forensic teams trace the attacker’s path, identify persistence mechanisms, and remove malware. Remediation includes resetting credentials, patching vulnerabilities, and sometimes rebuilding systems from scratch.

In my experience, success against APTs comes from reducing attack surface and improving response times.

One firm cut average dwell time from 200 days to under a week by evaluating MSSP versus in-house SOC options and investing in threat intelligence and regular red teaming.

The hardest part is spotting the quiet, slow moves, lateral propagation, credential harvesting, internal spread. APTs hide in plain sight, using legitimate credentials and blending with normal traffic.

Frequent tabletop exercises, up-to-date threat group cards, and strong vendor partnerships help organizations stay ahead. It is a constant process.

Looking ahead, APTs are only getting more sophisticated.

Expect the same groups, APT28, APT29, Lazarus, APT41, to remain active, but their campaigns will target new sectors, like logistics and IoT providers.

Attackers increasingly use artificial intelligence to automate reconnaissance and evade detection. Supply chain attacks will grow, especially as software dependencies multiply.

AI-driven malware can adapt in real time, changing attack patterns to avoid signature-based tools.

As companies move to the cloud and deploy IoT devices, new vulnerabilities emerge. APTs are already probing these systems for weak spots.

Unpatched IoT devices, poorly configured cloud storage, and remote work tools all expand the attack surface.

Ongoing vulnerability management, regular IoT and cloud security audits, and robust incident response plans are necessary.

The best defense is collective. Collaboration between companies, government agencies, and cybersecurity vendors is key.

Sharing threat intelligence, attack signatures, and best practices helps everyone respond faster.

APT groups are not going away. If anything, they are getting smarter and more patient. For anyone tasked with cyber defense, the lesson is clear: invest in detection, train your people, and prepare for the day you find evidence of a persistent adversary already inside.

The only way to fight patience is with vigilance, never assuming you are safe just because you have not seen an attack.

If you’re responsible for security, don’t wait. Start now with expert consulting tailored for MSSPs, streamline your operations, reduce tool sprawl, and sharpen your defenses.

APT groups sometimes launch a denial of service distraction to pull attention away from a bigger threat, like a strategic web compromise.

While defenders focus on the noisy attack, stealth threat actors sneak in using custom malware, cyber intrusion tactics, and command and control setups to reach their true targets.

While some APT groups focus on cyber sabotage and espionage campaigns, others engage in financial cybercrime.

These hacking campaigns may overlap, using advanced malware and malware loaders to hit both economic systems and high-value infrastructure, all while avoiding attribution through stealthy persistence and evasion techniques.

During cyber warfare, APT groups conduct cyber intelligence operations to spy on military, political, or industrial targets.

Using spear phishing, remote access trojans, and credential harvesting, they infiltrate systems and collect data. These stealth threat actors often work as part of broader espionage campaigns.

APT groups use living off the land tactics to blend in with regular system activity, making them harder to spot. That’s why cyber resilience, being prepared to recover and respond, is key.

It helps organizations withstand threats even when advanced persistent threat actors are already inside the network.